Note: Chief Avsec is away from the home office this week serving as an Instructor/Counselor at the 2015 WVU Junior Fire Camp (For the first time!). So for this week, here’s a replay of a popular and very pertinent post from a while back.

By: Robert Avsec, Executive Fire Officer

Take a few minutes and view this video:

Firefighters Injured in Collapse During Overhaul

This fire (in the video) is a great example of the importance of conducting a complete assessment of a building’s structural integrity  before beginning overhaul or allowing anyone into a building where an aggressive interior fire attack was started (and firefighters were subsequently withdrawn) or fire operations were conducted from the exterior (defensive tactics).

before beginning overhaul or allowing anyone into a building where an aggressive interior fire attack was started (and firefighters were subsequently withdrawn) or fire operations were conducted from the exterior (defensive tactics).

At first, this blog was going to be about what I observed in the video that had me questioning why personnel were inside this building for overhaul. Obviously, it’s hard to make a complete assessment based on the limited and edited video, but my size up indicates that there’s a tremendous amount of heavy and dark (gray and black) smoke issuing under pressure from everywhere on the fire building. As such, the building must have sustained a significant amount of degradation to its structural integrity, that is, its ability to resist gravity.

But as I viewed the video several more times, I had another thought: Why did the Incident Command chose to initiate an offensive attack based on the smoke conditions and occupancy upon their arrival?

Such an observation (heavy smoke issuing from multiple locations on the exterior) indicates a high level of risk to me because there’s likely zero visibility inside the structure. Firefighter disorientation, which is loss of one’s direction due to the lack of visibility in a structure fire, is one of fire fighting’s most serious hazards and according to the National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), and typically precedes a firefighter fatality.

The U.S. Firefighter Disorientation Study, conducted by Captain Willie Mora, San Antonio, Texas, Fire Department, reviewed 23 firefighter fire ground deaths occurring over a recent 16 year period (1997–2001).

See Related: U.S. Firefighter Disorientation Study

The authors of the study collected and analyzed data in an effort to determine how firefighter disorientation factored into firefighter fatalities caused by smoke inhalation, burns, and traumatic injuries.

The data collection set included the following areas and types of information.

- Information about the Structures Involved: Occupancy Type; Construction Type; Structure Size; Age of structure; Built-in Fire Protection Provided; and Structural Features.

- Smoke Conditions Showing on Arrival

- Fire Showing on Arrival

- Fire Conditions after Arrival

- The Strategy and Tactics Employed

- The Action That Occurred in the Structure

I sincerely hope that this officer was not standing there looking into the smoke because firefighters were in this structure. What is the risk/benefit on this?

The study’s authors determined that disorientation fires occurred in several different occupancy types, construction types and structures of different ages and sizes. Their research did, however, reveal many similarities in other areas which the study team defined (and these terms are useful in understanding how firefighters become disoriented and die or become injured when conducting interior fire control tasks.

Opened Structure– An Opened Structure has windows or doors of sufficient number and size to provide for prompt ventilation and emergency evacuation. An Opened structure may or may not have a basement.

Enclosed Structure– An Enclosed Structure is one in which there is an absence of windows or doors of sufficient number and size to provide for prompt ventilation and emergency evacuation. An Enclosed structure may or may not have a basement.

Prolonged Zero Visibility Conditions– Prolonged zero visibility conditions are heavy smoke conditions lasting longer than 15 minutes.

Since these prolonged zero visibility conditions exceed the approximate breathing-time of a working firefighters’ self-contained breathing apparatus, (30-minute rated), these conditions should be considered extremely dangerous should disorientation occur.[1]

Mora’s research determined that 23 percent of firefighter fatalities from disorientation occurred when a fast and aggressive interior attack was made on an “opened structure”.

When fast, aggressive interior attacks occurred in “enclosed structures” the fatality rate rose to 77 percent. Many of these occurred in “marginal” or rapidly changing conditions in which the firefighter should not have been in the building.

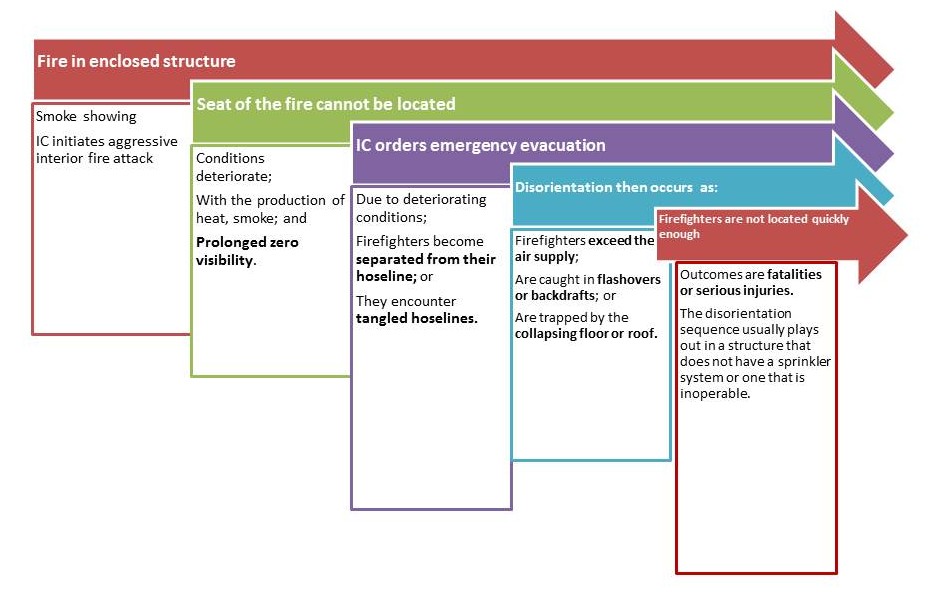

The Disorientation Sequence

A sequence of events that caused firefighters to become disoriented occurred in each of the 17 incidents studied. In general, the sequence unfolds as follows:

Source: Mora, W.R. [Internet] U.S. Firefighter Disorientation Study: 1979 – 2001. San Antonio, TX. Available from: http://www.colofirechiefs.org/ffsafety/FirefighterDisorientationStudy.pdf

Why Do We See the Disorientation Sequence Repeated Today?

Have you ever heard the expression, “Like rearranging the deck chairs on the Titanic,” to describe a situation where the response to the conditions is inappropriate? What was being gained by having these two firefighters “up close and personal” with a fire of this magnitude? And with a hose line that’s capable of 200 gpm for fire flow at best?

- Most firefighters “cut their teeth” learning to fight fires from the interior of the structure, aka, Offensive Strategy. From Day 1, those same firefighters are indoctrinated about the “virtues” of a fast and aggressive interior attack at any structure that’s been deemed “safe” to enter by the Incident Commander.

- Fire officers learn from Day #1 that one of the critical initial size-up factors at any structure fire is the amount of smoke showing from the structure on arrival. Light, moderate, or heavy smoke are common smoke conditions in which an officer would initiate a quick interior attack to locate and extinguish the seat of the fire or to conduct a primary search.

But that’s not what the data says we should do. Mora and his colleagues found these were the same smoke conditions that were reported by the first arriving officer at 94% of the enclosed structure fires that ultimately resulted in disorientation. The root of the disorientation problem in the fire service is the lack of knowledge about the extreme danger posed by enclosed structures and the disorientation sequence.

It is clear that the cause of firefighter fatality in the categories of smoke inhalation, burns, or trauma attributable to disorientation is directly linked to specific types of structures. These structures include: Enclosed Structures, Enclosed Structures with basements, Opened Structures with basements and High-Rise hallways (Enclosed Hallways). Enclosed Structure fires will also occur in any structure in spite of the occupancy type, construction type, size, or age of the structure or whether or not it is occupied or vacant. It must be noted however, that disorientation has occurred in Opened Structures, but they seem to occur only occasionally.[2]

We Can—and must—Do Better

It’s only 7 more days until the year 2014 rolls up on the calendar and I can’t believe I’m about to write about recommendations that Mora and his colleagues wrote up in 2003 (Yes, ten years ago!).

- Firefighter training—beginning with entry-level and continuing for incumbent training—must emphasize the extreme danger of disorientation associated with firefighting in enclosed structures.

- Firefighters must become informed and educated that there is no default mode for firefighting operations, aka, an aggressive interior attack immediately on arrival at every fire.

- Fire officers must learn that an offensive strategy may be ineffective and unsafe in many cases. Every fire situation requires that the Incident Commander develop an incident-specific Incident Action Plan (IAP) based upon their size-up of the incident conditions.

- Fire departments should revise their Standard Operating Guidelines (SOGs) to avoid the disorientation sequence that leads to fatalities. Those SOGs should be rewritten adopting new strategy and tactics, including an Enclosed Structure SOG that calls for utilization of a Cautious Interior Assessment instead of a quick interior attack at the outset of the incident.

A Cautious Interior Assessment is a process whereby the first engine company may enter the structure with a Thermal Imaging Camera and charged hose line, with an established water supply and back up companies with thermal imaging cameras, to look into the structure to locate the seat of the fire. After the seat of the fire is located the Officer will decide, based on interior conditions, whether to make an aggressive interior attack and ask for back up, decide to make a Short Interior Attack from a different part of the structure or to conduct a defensive operation…when distances are excessive, arrangement or amount of contents hazardous and life safety is not an issue, it may be safer to initiate a Short Interior Attack in hazardous Enclosed Structures.

A Short Interior Attack involves advancing handlines to the seat of the fire using the shortest distance from the exterior. This may involve using existing windows or doors or using breaching techniques if needed. Initiating a short interior attack increases safety by minimizing the distance between the exterior and the seat of the fire to maximize efficiency of air supply, prevent hose line separation, disorientation, and avoid exposure to flashover, backdraft or collapse. If breaching is not safe or cannot be accomplished in a timely manner, a defensive attack should be made.[3]

Getting back to the collapse. That much smoke for a long period of time tells me that the fire has taken significant control of the building and has severely degraded its capability to resist gravity because the fire has extended to multiple concealed spaces in the walls and floor. Once that fire was extinguished, overhaul operations should have been postponed until a certified building inspector completed a structural evaluation of the building.

Getting back to the collapse. That much smoke for a long period of time tells me that the fire has taken significant control of the building and has severely degraded its capability to resist gravity because the fire has extended to multiple concealed spaces in the walls and floor. Once that fire was extinguished, overhaul operations should have been postponed until a certified building inspector completed a structural evaluation of the building.

I’m sure that these comments will likely elicit more than a few comments along the lines of: “You weren’t there, so don’t judge others”; “It’s easy to be a “Monday Morning” Quarterback.” I’ve heard those and many others over the years, and I’m not particularly concerned. I am, however, concerned that we seem to be failing in the fire service to make these changes in the way we conduct our fire suppression operations.

If we cannot objectively analyze our own actions and the actions of others for the purpose of learning and not repeating mistakes, can we really call ourselves professional firefighters?

References

[1] Mora, W.R. [Internet] U.S. Firefighter Disorientation Study: 1979 – 2001. San Antonio, TX. Available from: http://www.sanantonio.gov/safd/PDFs/FirefighterDisorientationStudy.pdf

[2] Ibid, p.5

[3] Ibid, p.6

Fire & EMS Leader Pro The job of old firefighters is to teach young firefighters how to become old firefighters!

Fire & EMS Leader Pro The job of old firefighters is to teach young firefighters how to become old firefighters!