By Robert Avsec, Executive Fire Officer

I’m not referring to individuals or teams that have attained the #1 status in their sport. Rather, I’m going to discuss the dearth of champions in fire and EMS departments who can turn the word champion (the noun) into champion (the verb).

In a 2016 article, Women and minorities in the fire service need champions, I wrote about the differences between a champion and a mentor.

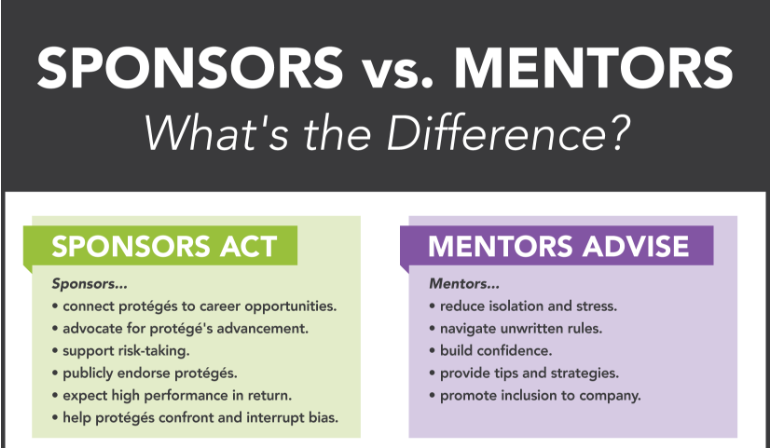

The key difference between mentors and sponsors is that mentors are “one-way streets”, giving their chosen mentee a gift of wisdom, time, and advice. Sponsorship requires reciprocity and commitment; sponsors serve as champions.

I personally like the term “champion.” It’s a term that Deputy Chief (Ret.) Jim Graham—who was both a mentor and champion for my career—frequently used regarding people, programs, and projects.

Fire and EMS departments will never achieve any sort of success sin reaching their goals towards becoming diverse and inclusive organizations until their white male leaders learn how to champion the efforts of the different people—Women, Blacks, Hispanics, Latinas, Asian-Americans, and people who identify as LBGTQ+–that they have successfully recruited for their fire and EMS departments.

Read Next: This is What a Fire Service Champion Looks Like

I recently had an in-depth interview with a woman (I’ll call her Athenia to protect her anonymity) who had made herself a successful fire service career in several different fire departments, rising to the level of chief officer. She did this by following “the rules” that white males have used successfully for years:

- Pursued her formal education.

- Attained CFO (Chief Fire Officer) designation.

- Completed EFOP (Executive Fire Officer Program) at the National Fire Academy.

- Took on the difficult work assignments.

- Worked with groups inside and outside of the department that she served.

In short, Athenia did all the “career development things” that have spelled success for white males in the fire service (And bear in mind I’m a 64-year-old who’s been a white male my whole life!).

And you know what she got for her efforts? A “target” on her back. A target for her white male superiors to “shoot at” when they became threatened by her success. Especially when that success meant popularity among the people (firefighters and fire officers) below her on the organizational chart, popularity not enjoyed by her superiors.

Such professional jealousy—Can there be any other word for it? —caused her to leave two fire departments because of the hostile work environment she was forced to endure. She would subsequently file lawsuits against both departments and prevail in those legal actions because the legal system saw the hostile work environment for what it was: sexual harassing behavior.

Read Next: ‘Women get tired of breaking the glass’: Why female chief officers turn to lawsuits

Later, she was subsequently recruited by another large municipal fire department by that fire department’s fire chief to join his department because of her knowledge, skills and abilities (KSAs) which his department was much in need of at the time.

So far so good, right? Wrong. Because once again, she joined a fire service organization that had no champions, not even the fire chief who brought her to the job in the first place.

She did the tough jobs she was brought in to do and did work beyond the scope of her assigned job title. And once again there was that “target.”

My superiors didn’t know how to talk to a woman unless it was to flirt. My deputy chief hardly spoke to me the entire time I was with the department. Even the fire chief who brought me into the department “threw me under the bus” when other officers above me began “shooting” at the target on my back. He never stood up for me, never supported me. He just let them keep shooting.

Today, Athenia is unemployed, having left that fire department for the same reason she left those other two fire departments, a hostile work environment. A hostile work environment where she was treated as a pariah. Where her demanding work and accomplishments—accomplishments that could only be viewed as reflecting positively on her organization—were not really acknowledged and celebrated, but only served to increase the size of the target on her back. She provided an example:

Our Police Department received a grant to develop a program to improve diversity and inclusion in that organization. Their leadership extended an invitation to the fire department to participate, and my deputy chief sent an email to our fire chief saying I was the right person for the job.

So, I took on that assignment and spent a year working with my colleagues in the Police Department and a number of groups from our department’s rank and file developing and implementing what we thought was a good and much needed program. My boss never spoke with me about my work and certainly never encouraged me during that time. And when the program was successfully implemented, the fire chief took all the credit.

How Long Will This Sh*t Go On?

Is it any wonder that the percentage of women in the fire service has never reached five percent? In fact, it’s lower than it was several years ago, hovering around four percent. In a 2021 article on FireRescue1.com, Fire service sexual harassment: Stop gaslighting women, start taking it seriously,

Firefighter/Paramedic Shelby Perket wrote:

I began to do some research to see if there had been any studies on sexual harassment experienced by women in the fire service, because I knew this was far too common than anyone would like to admit. What I found was heartbreaking.

Perket, S. Fire service sexual harassment: Stop gaslighting women, start taking it seriously.

What Perket found was A National Report Card on Women in Firefighting, the report from a study conducted by Hulett and Associates for the International Association of Women in the Fire and Emergency Services. The study’s authors, Hulett, Bendick, Jr., Thomas, & Moccio, described the study’s methodology:

This significant report represents the results of confidential written questionnaires returned by 675 male and female firefighters in forty-eight states, surveys of 114 departments nationwide, in-depth interviews with 175 female firefighters and case studies in Kansas City, Los Angeles, Seattle, Minneapolis and Prince William County, Va.

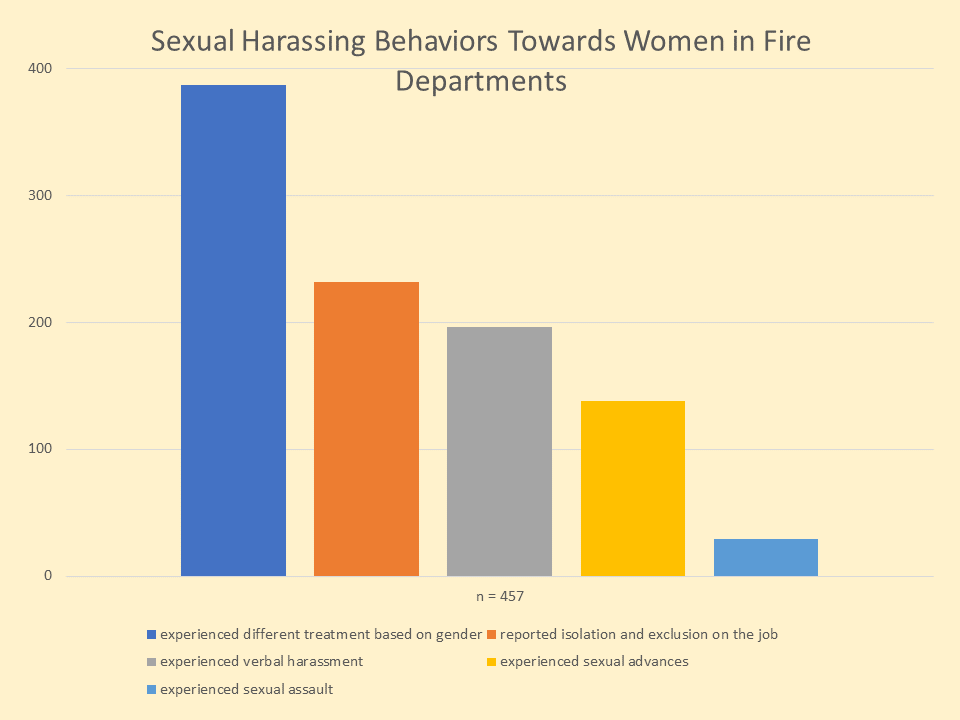

Perket wrote, “Of the 457 female firefighters interviewed, 84.7% stated they had experienced different treatment based on gender, 50.8% reported isolation and exclusion on the job, 42.9% experienced verbal harassment, 30.2% experienced sexual advances, and 6.3% experienced sexual assault.” (See Figure 1 below).

We’ve now been talking about improving diversity and inclusion in the fire service for several decades. And yet we’ve not made any measurable progress in the number of non-white, non-male members serving in our fire and EMS departments.

Secretary of the Navy Ray Mabus presided over the ceremony and administered the oath of office.

Adm. Howard is the first female four-star in the 238-year history of the U.S. Navy. “Michelle Howard’s promotion to the rank of admiral is the result of a brilliant naval career, one I fully expect to continue when she assumes her new role as vice chief of naval operations, but also it is a historic first, an event to be celebrated as she becomes the first female to achieve this position,” said Mabus. “Her accomplishment is a direct example of a Navy that now, more than ever, reflects the nation it serves — a nation where success is not borne of race, gender or religion, but of skill and ability.”

When fire departments do get members of the minority group in the door, they frequently don’t do a decent job of making inclusion a priority. Lest one think that Athenia is an exception or a “bad apple”, let me put that assumption to rest. I know of at least a dozen women officers—several of whom were chief officers—who have left the fire service for the same reasons that she did.

Our military services have certainly figured out this conundrum. They’ve become adept at not only getting women in the door, but equally adept at creating culture and systems where they can become actively engaged in the organization and develop their potential talents as far as their dreams take them.

Fire & EMS Leader Pro The job of old firefighters is to teach young firefighters how to become old firefighters!

Fire & EMS Leader Pro The job of old firefighters is to teach young firefighters how to become old firefighters!