By: Robert Avsec, Executive Fire Officer

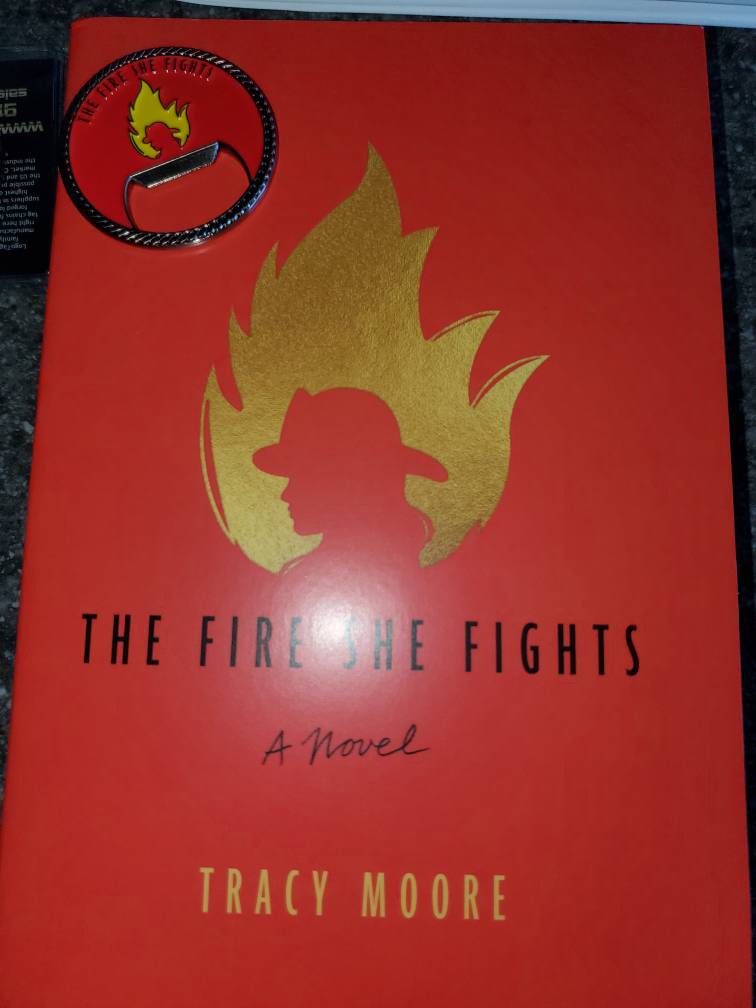

My fire service colleague and first-time author, Tracy Moore, wrote a blog to promote her debut novel, The Fire She Fights. Here’s an excerpt:

When I saw my professor’s name, from 35 years ago, flash on my phone I felt nervous. I remembered him as the guy who cared about his students. He was playful—I believe because he realized we were still young. I answered his call.

His voice was just as I remembered, and I immediately felt at ease. He wanted to talk about my newly published novel, The Fire She Fights.

Then he dropped the bomb. “My neighbor is a firefighter. I told him about your book, and he said, ‘I don’t believe in female firefighters’.”

The argument I’ve heard most: women just aren’t strong enough to do the job.

My professor defended me. When the firefighter neighbor insisted that a female couldn’t pull him out of a fire, my professor argued, “I believe this one could, or she would die trying,” he said.

Tracy Moore, WHY ARE THERE SO FEW FEMALE FIREFIGHTERS?

Come on, it’s 2022!

How much longer will we in the fire service allow this myth to survive? The fact is, there are few women or men that could rescue a downed firefighter alone.

After the loss of Firefighter Brett Tarver in a supermarket fire in 2001, the Phoenix (Ariz.) Fire Department, with assistance from Dr. Ronald Perry of Arizona State University, conducted a series of studies to learn how to avoid such a tragedy in the future. In replicating the layout of the supermarket and conducting real-time evaluations, it took an average of twelve firefighters to rescue one downed firefighter.

The study results, published in a December 28, 2010 article, also found that:

- One in every five rescuers needed to call their own Mayday

- It took an average of eight to nine minutes for a rapid intervention team (RIT) to reach a downed firefighter

- It took an average of 22 minutes to find, package, and extricate the firefighter in distress.

Those results were obtained in conditions where there was no high heat and smoke that would be encountered on the real fireground. If these results are not believable to a reader, I would challenge them to keep times and data from their own RIT training exercises and compare them to this data. They will undoubtedly be remarkably similar.

Jeffrey Pindelski, The Rapid Intervention Reality of Your Department – Part 1

We did just that in a series of evolutions conducted by the organization where I served for 26 years, the Chesterfield (Va.) Fire and EMS Department. You can also check here as we are using a vacant warehouse building, we conducted those evolutions on twenty-seven different days as part of our quarterly fire company in-service training. And yes, our results were right in line with those from the Phoenix Fire Department studies.

Our Lessons Learned

When conducting an operation to find and remove a distressed firefighter in a large structure, we learned several valuable lessons that we later incorporated into our fire ground SOGs, particularly our RIT SOG. Those lessons included:

- Search techniques commonly used in residential dwellings (e.g., crawling on hands and knees while keeping contact with a wall) are ineffective and inefficient. Instead, our firefighters found it more efficient and effective for a two-firefighter team to tie-off a lifeline at the entrance and then stand erect as they “probed” their path using a six-foot pike pole (much like a visually impaired person uses a cane).

- It’s difficult to use the sound coming from an activated PASS alarm to locate a downed firefighter in a large open structure. Our firefighters learned that, by covering one ear with their gloved hand, they could effectively eliminate one direction (e.g., to their left) from which the PASS sound was not coming from. By repeating this, they could effectively “narrow down” the area they had to continue probing and locate the distress firefighter more quickly.

- Once the downed firefighter has been located, the team must quickly (1) ensure the firefighter’s SCBA facepiece is still in place, (2) assess whether they are breathing, and (3) use the transfill capability on their SCBA to give the distressed firefighter breathing air.

- While this assistance is being provided, a second two-firefighter team must be deployed to follow the lifeline while bringing equipment necessary to (1) keep the first team supplied with air (e.g., fresh SCBA cylinders) and (2) equipment and tools necessary to extricate the downed firefighter from the structure (e.g., webbing for dragging, a rescue stretcher, forcible entry tools).

Depending upon the degree of work that needs to be accomplished to package and move the firefighter from the building, additional two-person crews may be required. And that’s where it can quickly become a 12-firefighter rescue operation.

Fire & EMS Leader Pro The job of old firefighters is to teach young firefighters how to become old firefighters!

Fire & EMS Leader Pro The job of old firefighters is to teach young firefighters how to become old firefighters!