By: Robert Avsec, Executive Fire Officer

So, your back! Welcome! And if you’re a new reader to my blog here’s the link to last week’s blog that’s the lead-in to this week’s post. (I strongly encourage you to read it before continuing here. Really!).

I recently spoke to a fire service colleague, Robert Creecy, former fire chief in Richmond, Virginia on this topic of interior structural firefighting. “Firefighters today are like the cowboys of the latter 19th century in America,” said Creecy. “The cowboys didn’t realize  that their way of life was ending with the completion of the transcontinental railroad and the expansion of other railroads across the western U.S.”

that their way of life was ending with the completion of the transcontinental railroad and the expansion of other railroads across the western U.S.”

Like those cowboys who couldn’t see (or accept) that the railroads would eliminate the long-distance cattle drives that were critical to their livelihood, today’s firefighters and fire service leaders are missing the “big picture” when it comes to firefighter exposures to smoke and the links to cancer. With each passing day we can no longer claim “We didn’t know!”

Today’s structure fire is a Hazmat Incident

So, we must respond to it as such, and not in a halfway effort. I spent almost all my 26-year career with Chesterfield (Va.) Fire and EMS Department as a member of our Hazardous Incident Team (hazardous materials response team) and the lessons I learned then are still with me now. Before any entries were made:

- We characterized the scene to identify the product involved and what the environment looked like where the release was taking place.

- We developed a chemical profile for the product involved.

- We identified the personal protective clothing that was compatible with the chemical profile.

- The entry team and backup team were provided with a clear set of tactical objectives prior to entry.

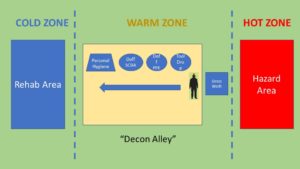

- The decontamination process (“Decon Alley”) was staffed and operational before any entry took place.

And those are just the high points that stuck in my memory. And it was typically for only one chemical! Can we really do anything less for firefighters who are exposed to hundreds of chemicals, chemical compounds, and carcinogens every time they are exposed to smoke? And let’s not forget that many of those chemical compounds don’t even exist until combustion takes place!

A new way

Last week’s blog provided my version of why interior structural firefighting—as we know it today–must go away and here’s what I propose to replace it with:

- Fire departments must make public fire life safety education and code enforcement key components of every firefighter and every fire officer job description. And then get out in the public and teach and inspect. Repeat.

- Fire departments must create effective and efficient marketing messages to let the community know that they are ceasing interior firefighting operations and why (More on that in a couple paragraphs).

- Fire departments must aggressively pursue the use of the “5-E’s” for preventing fires: Engineering, enforcement, education, economic incentives, and emergency preparedness to change the culture in the U.S. from one where communities are expected to extinguish fires when they start to a culture where having a preventable fire is abnormal.

A culture where the individual is held legally and financially accountable for not preventing a fire in their home or business. Just like the individual driver of a motor vehicle is responsible for not having a crash and faces financial and legal sanctions if they do.

See: Fire Prevention and Suppression: The Fire Service’s Identity Crisis

New emergency response paradigm—Phase I

For all interior structure fires, firefighters wearing structural firefighting PPE and SCBA will suppress the fire with a transitional attack from the structure’s exterior and control the fire’s flow path.

They will not enter the structure unless there is a clearly visible and endangered occupant that requires extraction. No interior searches! Sounds harsh? Consider these two scenarios:

Scenario A: Occupied structure with working smoke alarms that are heard by firefighters. Given that today’s “window of escapability” (time from activation of a smoke alarm until interior conditions are incompatible with human life) is three minutes or less, if the occupants were not alerted and out of the house already they are DEAD! (If it takes you and your crew 5 minutes to arrive–after you leave the station–you do the math).

Scenario B: Occupied structure without working smoke alarms with fire heavy smoke showing from the structure. Any occupants are DEAD.

Thermal imaging cameras (TICs) will be used to conduct a 360-degree assessment of the structure to identify additional hot spots from the exterior of the structure to be suppressed with exterior fire streams.

TICs with the capability of rendering temperature readings in the structure will be used to determine when interior temperatures are below 200 degrees F.

New emergency response paradigm—Phase II

Once the atmosphere has been cooled to < 200-degrees F, and visibility improved, loss reduction technicians (LRTs), nee firefighters, will enter the  structure. Those LRT’s will not be wearing structural firefighting PPE, but instead will be protected wearing a Level A fully-encapsulated hazardous material suit as they work to conduct overhaul and fire investigation for origin and cause.

structure. Those LRT’s will not be wearing structural firefighting PPE, but instead will be protected wearing a Level A fully-encapsulated hazardous material suit as they work to conduct overhaul and fire investigation for origin and cause.

The incident commander will determine the appropriate number of personnel that are needed for: (1) an initial entry team to do the work; (2) an equal number of personnel equipped and ready to provide relief for the initial entry team; and (3) an appropriately equipped RIT composed of at least three members.

The incident commander must ensure that it least a gross decontamination location is set up in the warm zone adjacent to the hot zone. A formal “Decon Alley” must be established as soon as resources are available.

The Incident commander must ensure that every structure fire is managed using control zones. All personnel should know: (1) where the zones are; and (2) what level of PPE is required in each zone:

- Hot Zone (Hazard Area): Level A, fully-encapsulated entry suit with SCBA.

- Warm Zone (Location of “Decon Alley”): Level B splash protection (e.g., Tyvek coveralls) with gloves and splash protection for face and head.

- Cold Zone (Location of Incident Command Post and support facilities): Station uniforms or civilian clothing.

We can’t not do this

We now know enough about the connection between firefighter exposures to the toxic chemicals, chemical compounds, and carcinogens present in today’s smoke encountered during interior structural firefighting to know that it is not right to continue putting firefighters into that environment.

Certainly not in today’s structural firefighting PPE which has never been designed for routine exposure to any hazardous material, particularly materials that are gaseous form.

Another factor is economics, and it cannot be denied. With a set of PPE costing about $2500 dollars, and a SCBA unit costing another $4000 or so, can any fire department really continue to put $6500 dollars or more per firefighter into such a toxic environment with no consistent and cost-effective method for rendering that equipment 100 percent safely cleaned and decontaminated?

The only way to stop exposing more firefighters to an increased risk of developing cancer–a risk that’s already greater than that of the public we serve–is to stop exposing them to the heat and toxic smoke of interior structural firefighting. Not limit it, implement gross decontamination after overhaul, or issue a second set of PPE or use disposable wipes after doffing PPE. Stop it. Period.

Many fire service leaders are probably thinking the same thing, but they can’t or won’t tell you that. I just did.

Fire & EMS Leader Pro The job of old firefighters is to teach young firefighters how to become old firefighters!

Fire & EMS Leader Pro The job of old firefighters is to teach young firefighters how to become old firefighters!