By: Robert Avsec, Executive Fire Officer

The St. Albans, West Virginia Fire Department is just one of a growing number of fire departments across the country that is finding itself in fiscal jeopardy.

A levy that helps fund the department, and that’s been on the ballot since 1951, failed. The St. Albans Fire levy comes up every 3 to 5 years and for decades has had the community’s support. “When it didn’t pass this time it was really pretty shocking because the community loves us and has always been super supportive of everything we’ve ever needed,” said Chief Steve Parsons.

On November 4, 2014 St. Albans voters rejected the levy, which supplies half of the $1.6 million budget for the fire department. That money helps fun the more than 1,500 emergency calls the department responds to each year. It also helps pay the salaries of the 22 full-time and 5 part-time firefighters serving the St. Albans area.

In Connellsville, Pennsylvania, the majority of Connellsville voters decided on Election Day 2014 that they want to eliminate Connellsville’s paid fire department and only remaining paid firefighter.

Providing fire protection as we currently know it is for the most part a very people, equipment, and facility intensive operation. Those firefighters, fire apparatus, and fire stations–and support facilities such as training centers and administrative buildings—represent a very significant fiscal outlay for most communities and that “bill” grows larger every year.

And increasingly, those communities are “balking”—at the voting booth or through decreasing donations to volunteer departments–when it comes to “paying” that bill.

When any service business or company finds itself in financial straits, its leadership only has a couple of options:

- Reduce the number of full-time positions (since personnel costs account for 75-90 percent of a business’s operating expenses) in the hopes that reduced expenditures can help get the business “back in the black”;

- Restructure the business to reduce the number and types of services that it provides;

- Find a willing buyer to purchase the company and its assets (and liabilities); or

- Go out of business.

When faced with inadequate fiscal resources, fire departments have universally employed Option #1 and/or to some degree Option #2. Option #3 has been employed by local leaders through the outsourcing of local fire protection to private sector organizations. Heretofore, Option #4 was only something that could happen to a volunteer organization. The times they are a changing.

What are fire departments to do?

In an earlier blog, I wrote of the need for fire department leaders to evaluate the current model for community fire protection, a model that is primarily a reactive service: firefighters and equipment waiting in a stationary location for notification of a fire. The time for evaluation has passed for those departments who are facing extinction because their communities can no longer afford to pay for the current model of fire protection.

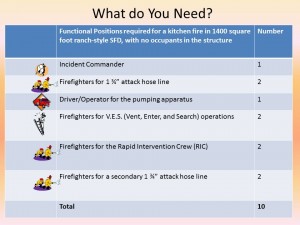

As Dr. Phil says, “It’s time to get real!” Fire departments must stop trying to provide a model of fire protection—one that’s predicated on saving lives and property through the reactive deployment of firefighters who implement an interior fire attack the majority of time—when the department does not possess the resources to do so safely, effectively, and efficiently according to accepted standards and practices, e.g., NFPA 1710 or NFPA 17.

If a department cannot provide such a response to a reported structure fire in their locality then they must restructure their operational model and tell their community what level of fire protection they are getting for their money. But stop putting the lives and welfare of fire fighters and citizens in jeopardy.

For those departments that continue to exist in face of diminishing resources, they should inform and educate their community that this is what they can expect if they call 911 because their house is on fire:

- If the fire is still in its incipient stage AND confined to the object of origin, e.g., the sofa in the living room, we will enter the building with a two-person crew to extinguish the fire with a second two-person crew as their required backup outside the structure. Once the fire is extinguished, we will provide the necessary salvage and overhaul necessary to prevent re-ignition or additional damage to your home.

- If the fire has progressed past its incipient stage, and has involved the room of origin, we will extinguish the fire to the best of our abilities from the outside of the structure. If and when we are able to extinguish the fire from the outside of the structure, we will provide the necessary salvage and overhaul necessary to prevent re-ignition or additional damage to your home.

- If the fire is a fully developed free-burning stage fire that has involved more than one room or multiple floors of the structure, we will we will extinguish the fire to the best of our abilities from the outside of the structure. If we are unable to extinguish the fire from the outside of the structure, and the fire continues to progress, we cease fire suppression operations on your home and focus our resources and efforts on preventing the fire’s spread to adjacent structures, e.g., your neighbor’s house.

Sound rather harsh? Sound unrealistic? So does closing fire stations and laying off firefighters. So does continuing to expose firefighters to increasing levels of risk of injury or death because of negligence on the part of building occupants, developers, and builders. So does continuing to increase the fiscal burden to local taxpayers to pay for an antiquated fire protection model that is reactive rather than proactive.

Fire service leaders keep saying that we need to “think outside of the box” and make better use of technology, but more increasingly expensive technology that supports the “wrong” model is not the answer. The current model still relies on putting a sufficient number of firefighters on the scene and if a fire department can’t do that its leadership needs to have the courage to truly restructure the level of service it provides, not just try to “continue business as usual” with less resources.

Fire & EMS Leader Pro The job of old firefighters is to teach young firefighters how to become old firefighters!

Fire & EMS Leader Pro The job of old firefighters is to teach young firefighters how to become old firefighters!